Like all the best ideas, this one popped into life unexpectedly.

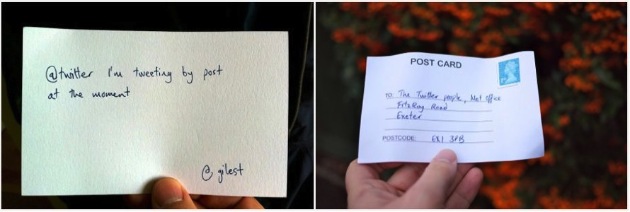

“How about doing Twitter by post?” I wondered to myself one morning.

“Would it work? How? Would it be fun?”

With the help of some willing collaborators, I decided to put it into action, and find out.

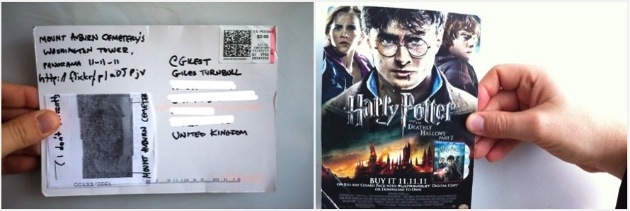

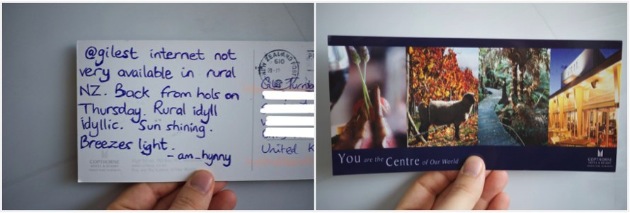

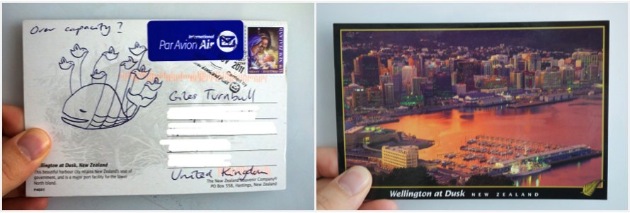

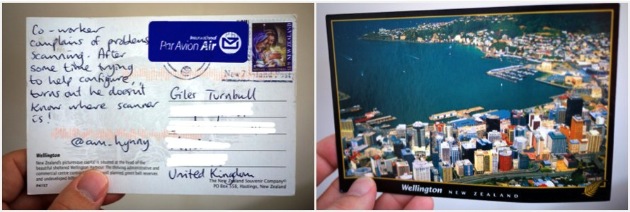

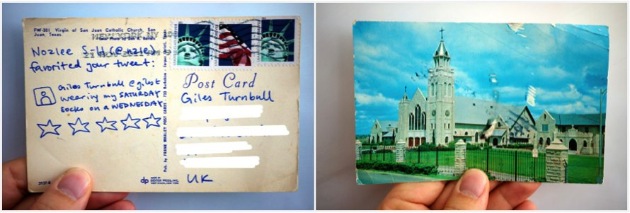

It worked like this: everyone involved sent me their postal address, while I headed down to the local Post Office and bought a job lot of stamps. Most of my helpers were here in the UK, but some were in the U.S., one in Australia, and one in New Zealand. I worried about how long the whole thing would take, what with having to wait for international posting times. But I needn’t have worried.

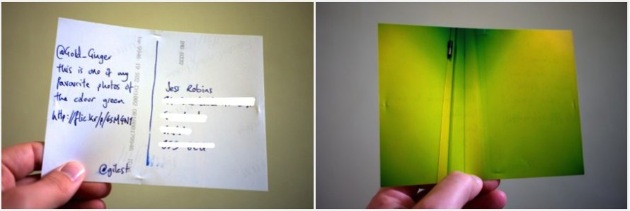

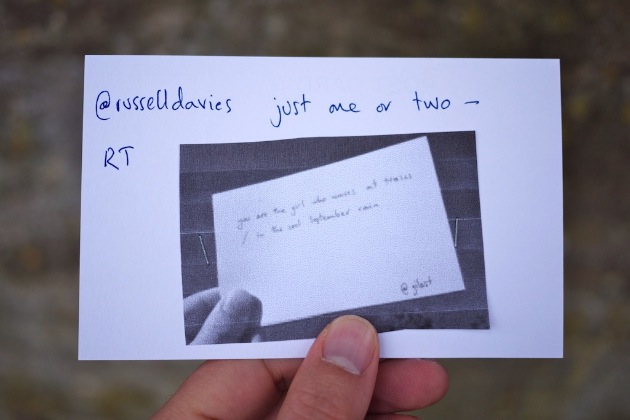

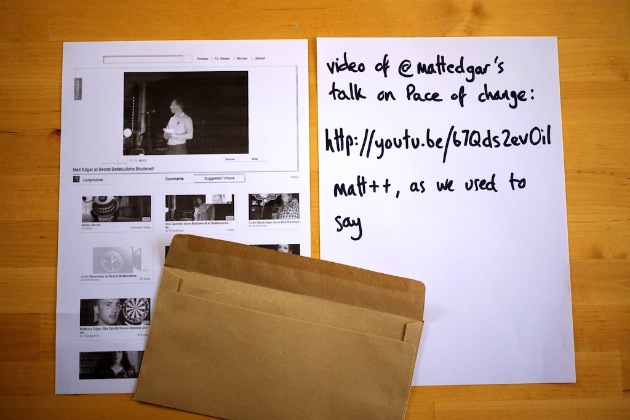

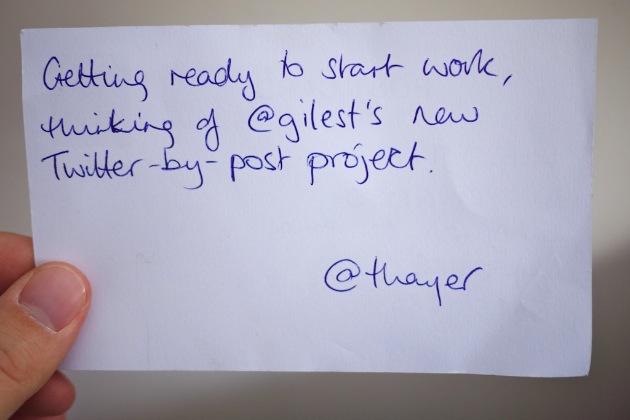

The mechanics of it took a while to work out. Most difficult was replicating my personal Twitter timeline—how could I post the same thing to everyone? Well, by writing it out lots of times.

For those “public” tweets, I wrote the same thing out 15 times, on 15 cards, and sent them to 15 different people. This took every moment as long as you might think; possibly a little longer.

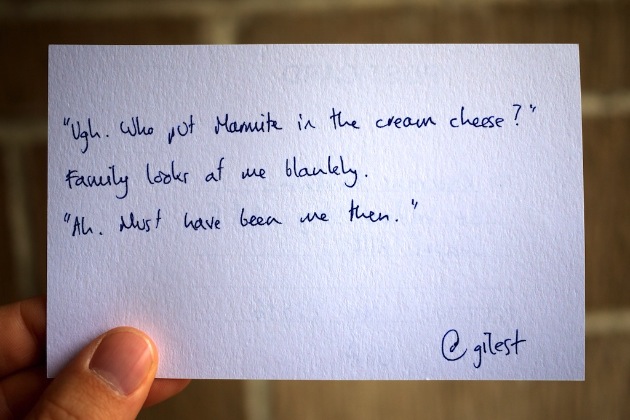

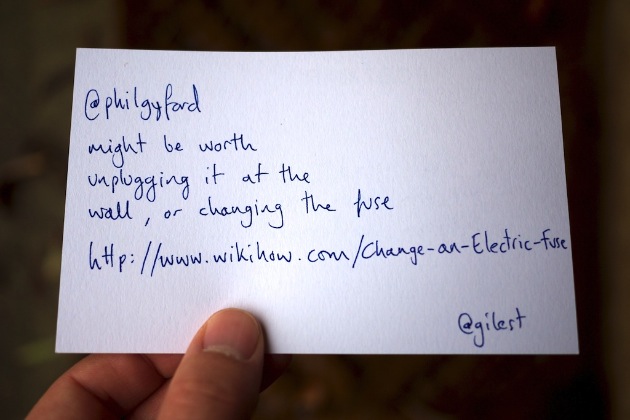

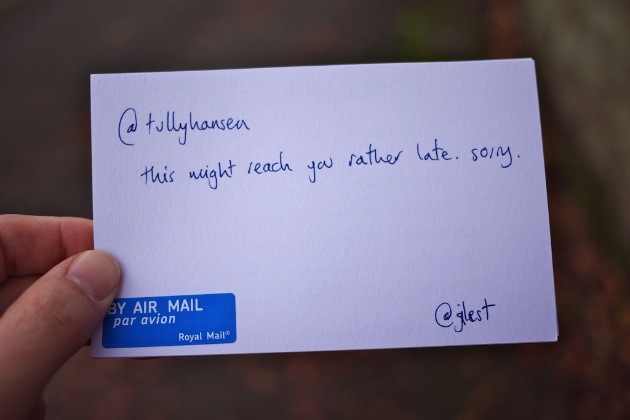

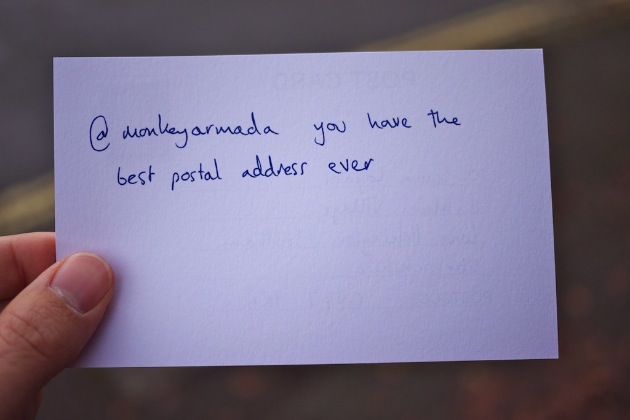

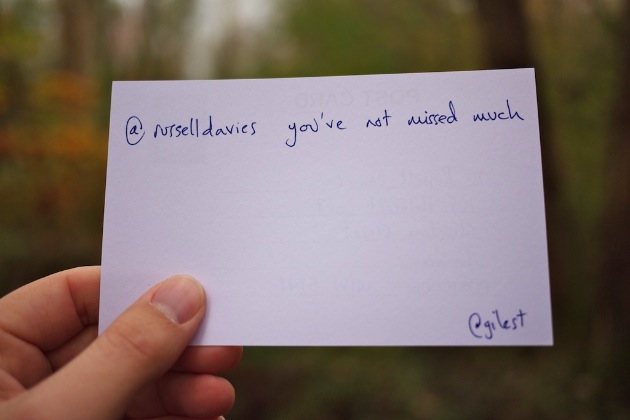

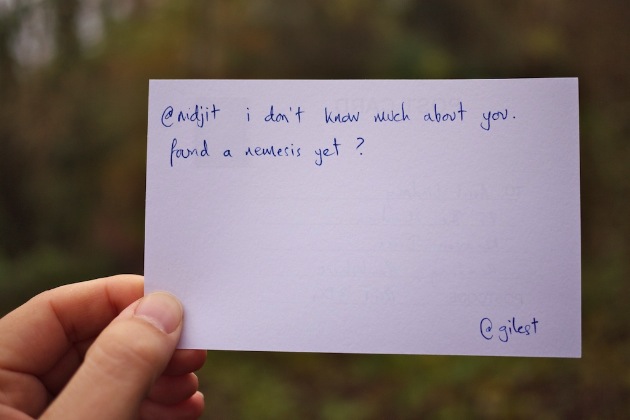

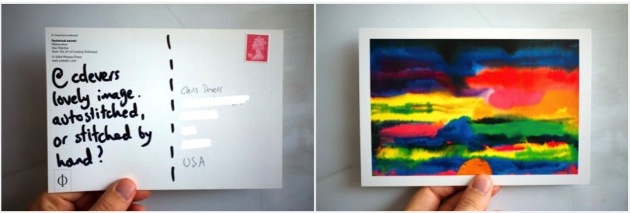

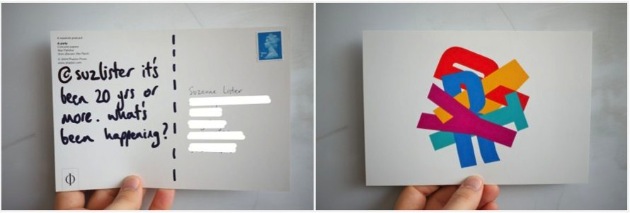

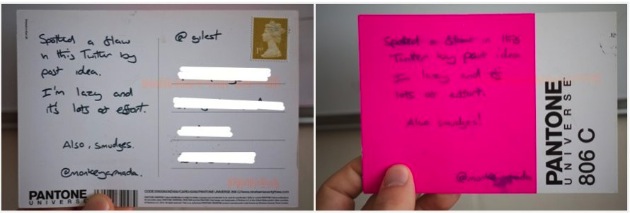

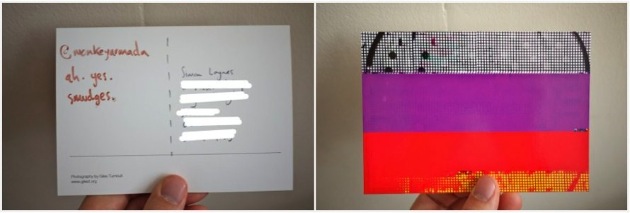

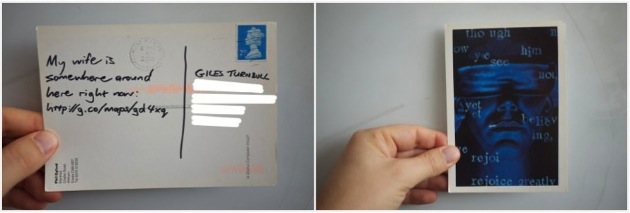

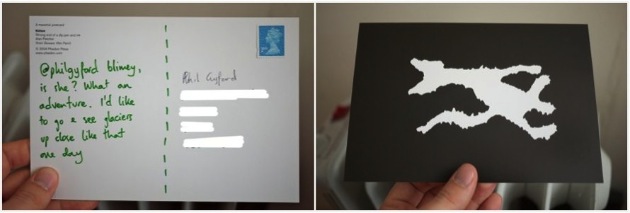

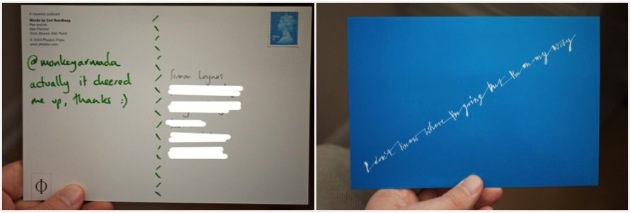

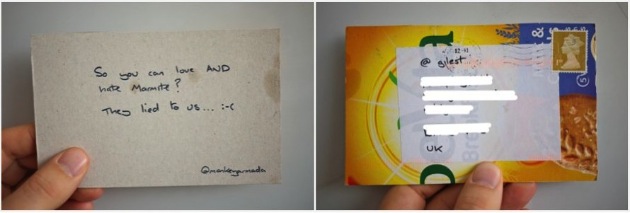

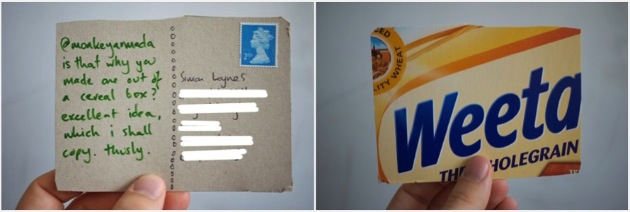

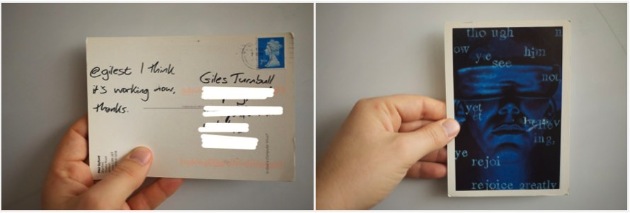

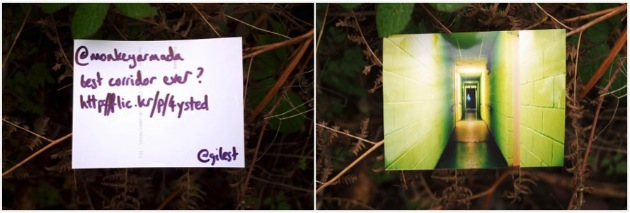

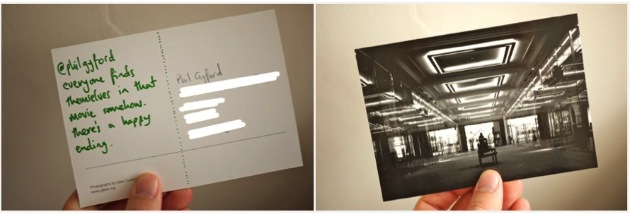

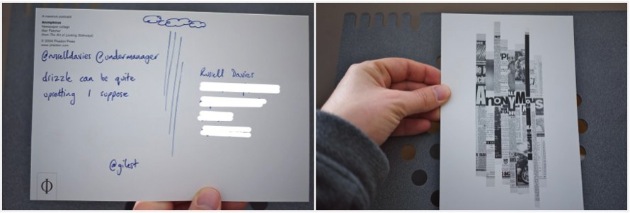

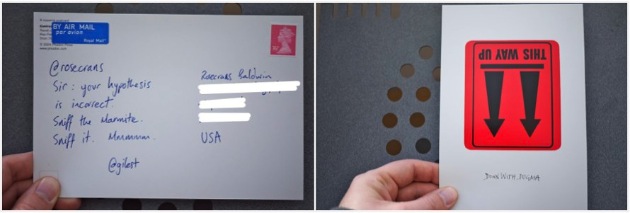

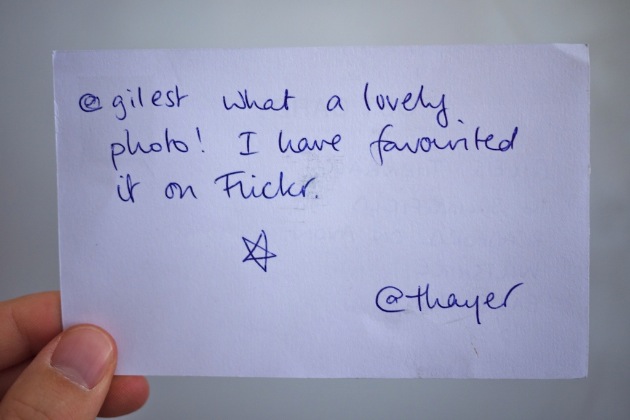

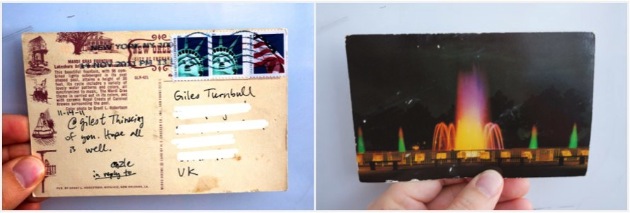

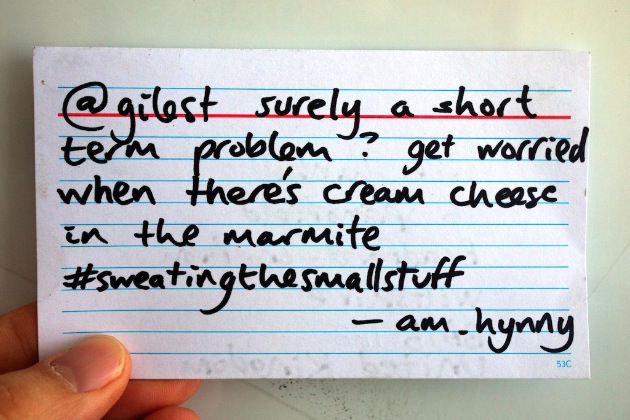

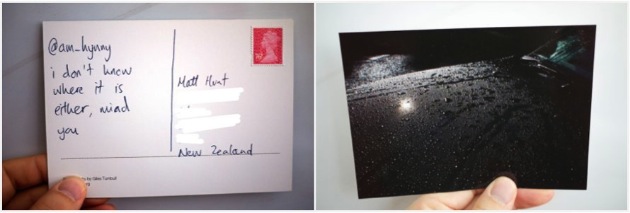

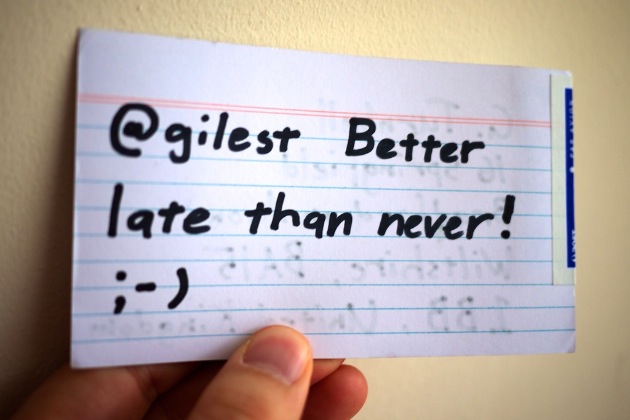

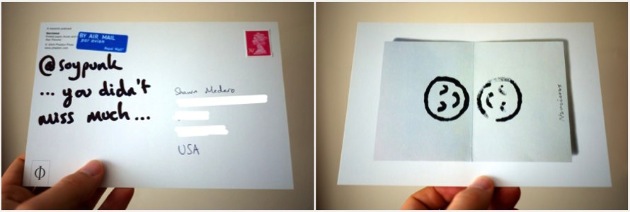

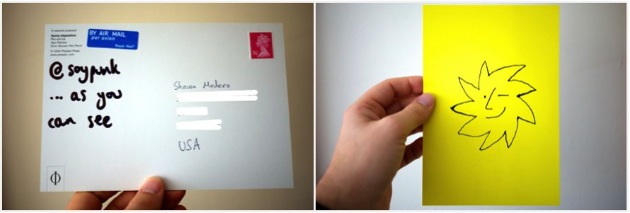

Other tweets were easier to do. The analogue of sending an @reply or a DM is simply sending one card to one person. Much simpler. Soon after starting the project, I settled on these as the best way of communicating.

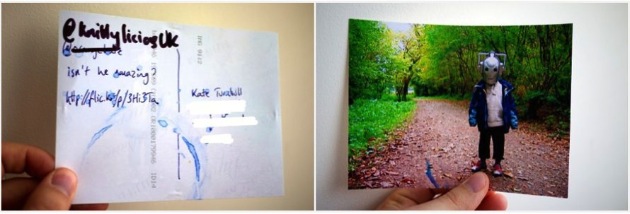

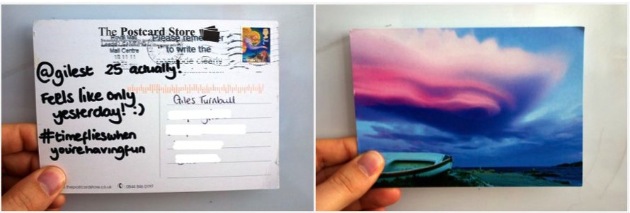

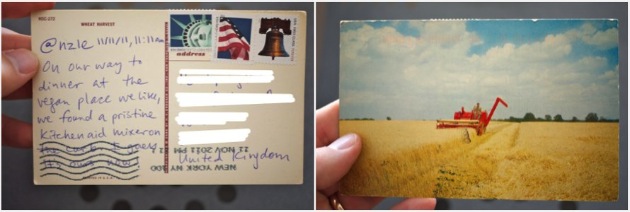

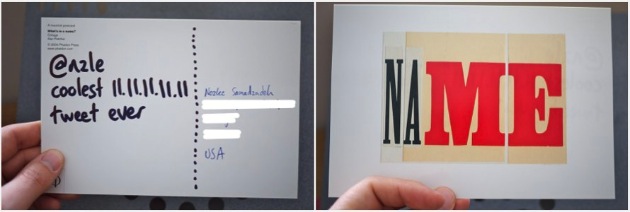

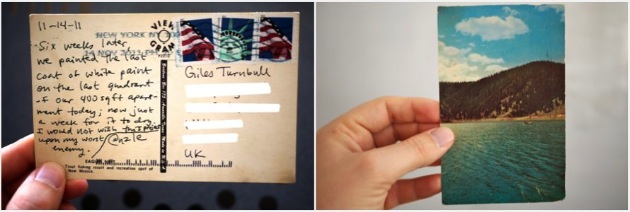

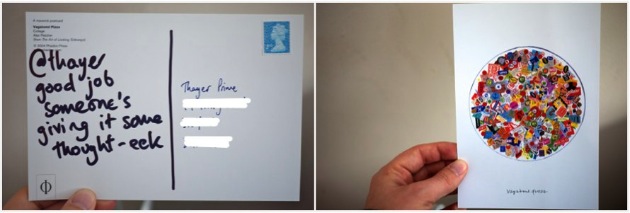

My wonderful collaborators were asked to do more than simply receive my ramblings through their letterboxes. I also asked them to reply with cards of their own.

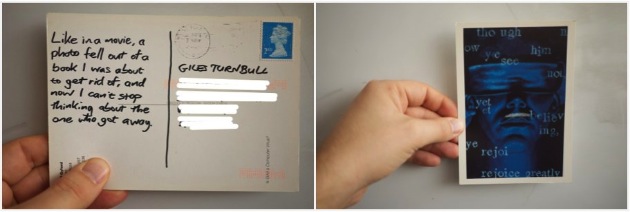

For the weeks that followed, my front door was my timeline. The sound of the postman (or postwoman, in my case) pushing cards through the letterbox became the equivalent of the little “DING” your Twitter client makes when you have new messages. Like Pavlov’s dog, I began to associate the sound of the postwoman’s approach with the arrival of new, unusually personal messages. I’d get jumpy with excitement, and rush out to the hall the moment they’d been delivered.

It’s true: While this experiment was under way, getting mail was fun again.

Ask your parents or your grandparents, and they might have a stash of old letters lurking in a box somewhere. You should look at them one day.

Back when people wrote letters, they didn’t have to be the long catch-ups that people tend to write today. We write long letters now because we hardly write letters at all, so we feel obliged to make them something special, to pad them out with lots of news. This makes them long and tedious to write, which means we’re disinclined to write letters; so we don’t write any at all, and post on Facebook instead.

But if you get the chance to look at some old letters—properly old, from the first half of the 20th century, or older—you’ll see that they weren’t always long screeds. In fact they were often kept short and to the point.

A bit like social media updates, actually.

A letter back then might simply ask one question. The reply would answer it. Just that. A letter might describe a single event, or pass on a single piece of news. I’m pregnant. Your father is dying. I was sent on patrol last night, and I survived. I love you. I still love you. I no longer love you.

Simple, short messages. That’s what the post was for. That’s why postal services were so frequent, and why there were so many deliveries.

The post mattered. People love updates.

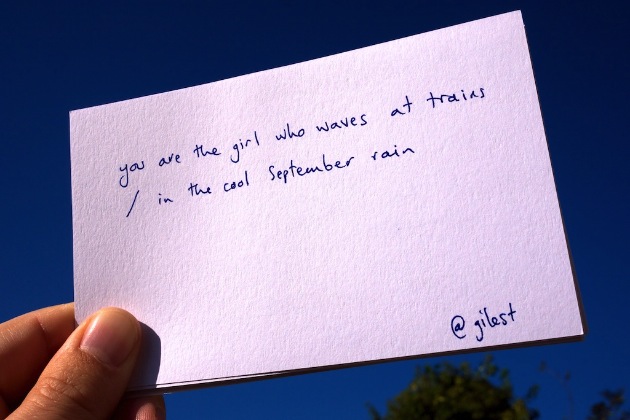

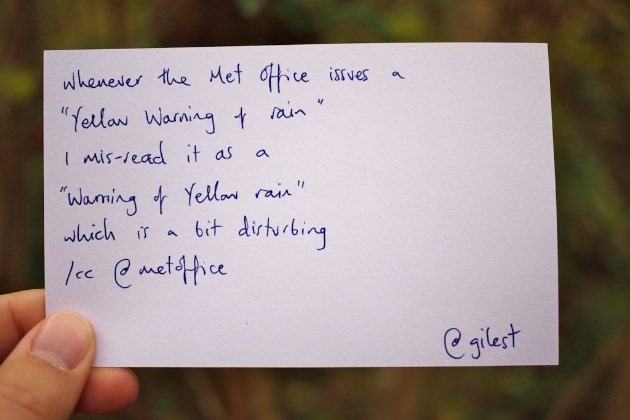

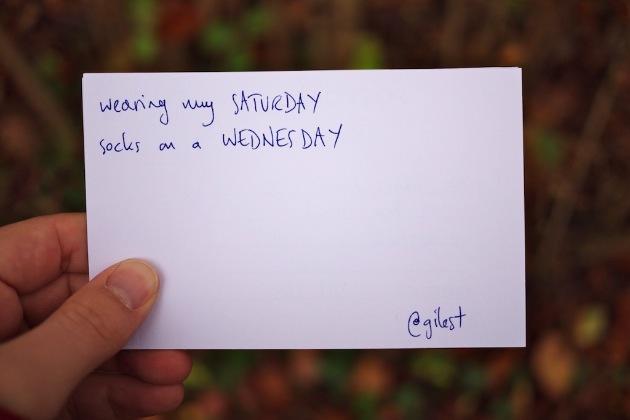

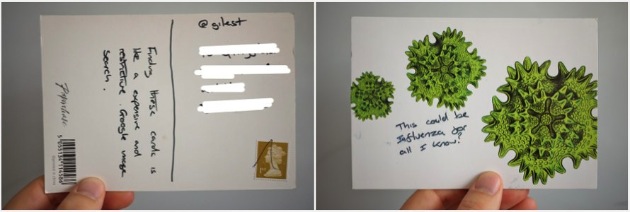

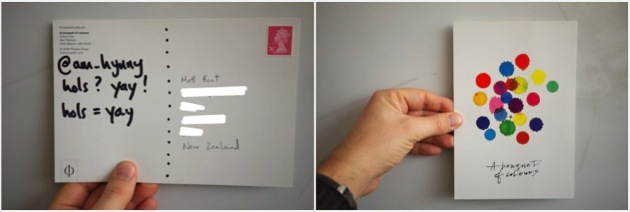

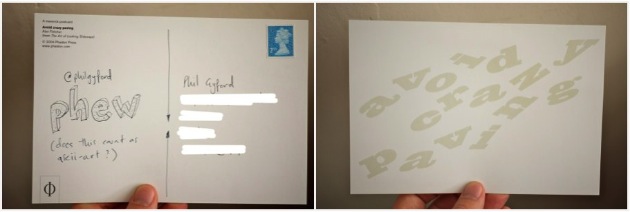

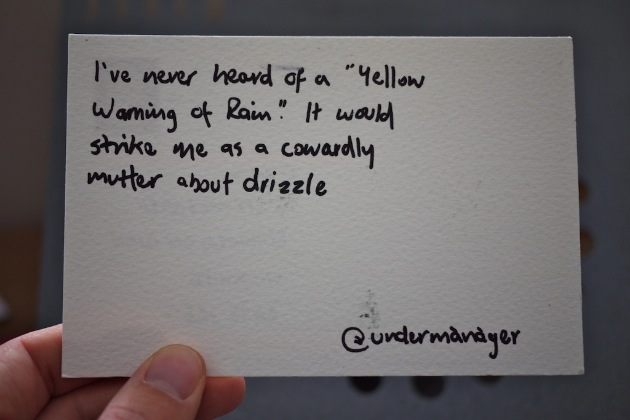

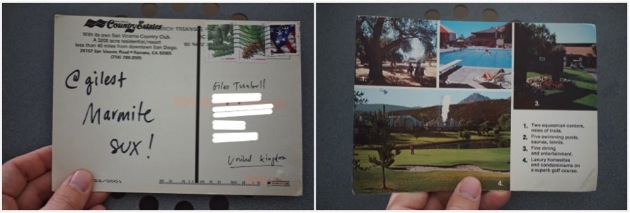

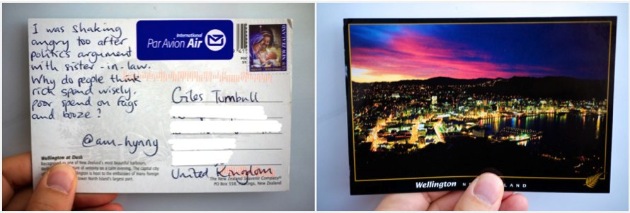

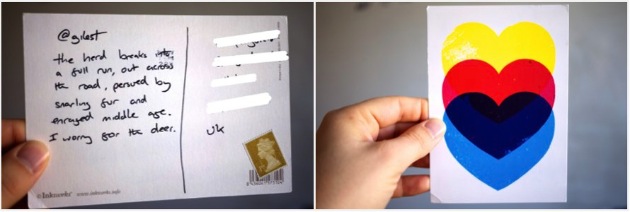

The modern postcard has become another obligation, something people feel they ought to send to loved ones from a vacation. “Look at us, we’re on holiday!” That’s a shame, because the postcard is the perfect medium for communicating briefly. Like Twitter’s restrictive word count, a postcard limits you.

Replicating Twitter via the postal system wasn’t an attempt to reject the internet—it was a way of celebrating it.

It limits the amount you can write, but not your imagination. As Twitter-by-post has proved.

In all of this, the intention wasn’t to escape the internet. There was no sense of trying to capture some kind of zen-like minimalism, to recapture simpler times of days gone by. No, none of that. I love the internet, after all. In all its frustrating, ever-changing, mutating, laugh-inducing, mind-provoking glory, the internet changed my career, my hobbies, my life.

Replicating Twitter via the postal system wasn’t an attempt to reject the internet—it was a way of celebrating it.

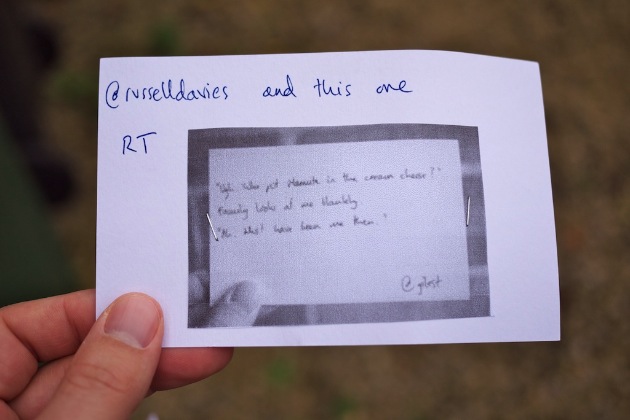

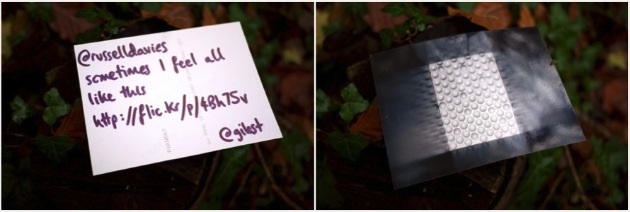

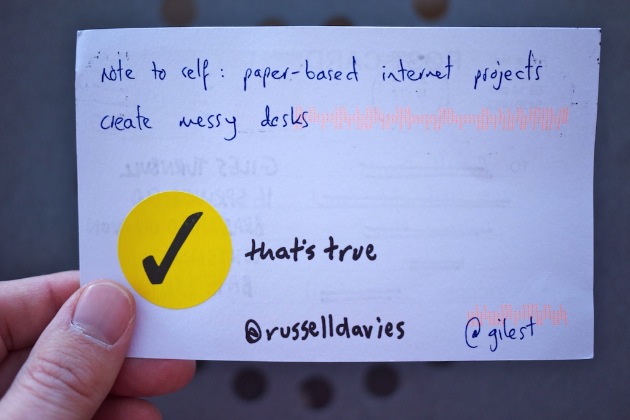

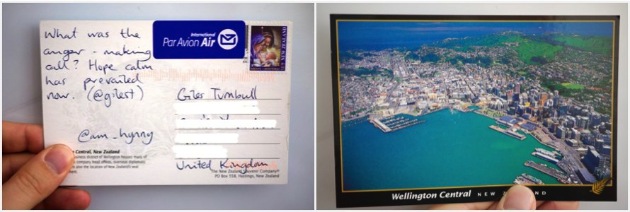

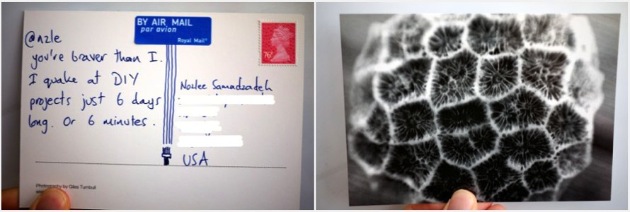

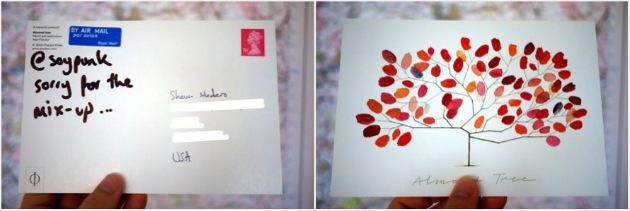

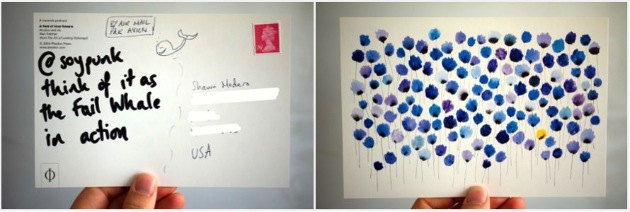

Even through the post, we talked. We sent links, locations, photos, and videos. We faved. We retweeted. We glimpsed the Fail Whale, and saluted her. The enforced time delay was no more inconvenient than Twitter’s enforced character count. Conversations took longer, but they made just as much sense. If anything, they felt more real. Now I have a pile of conversations on my desk. I can touch them, or shuffle them.

Tweeting by post made me appreciate the online and the offline. Brevity is a good thing, but there’s no reason we should only be brief on Twitter. The internet is a marvelous thing, but so is cheese, so are close friends who know your opinions and respect them, so is a glass of fine English ale. So is getting postcards from interesting people, because it makes your letterbox come alive.

You in turn can post your life through other people’s letterboxes, and you should, every now and then. It’s more fun than a fave, or a DM, or an @reply.

Big thanks to the merry band of Twitterers who agreed to be subjected to my ramblings by post, and who cheerfully sent their own ramblings by return: @cdevers, @soypunk, @bamblesquatch, @nzle, @philgyford, @thayer, @knittyliciousuk, @russelldavies, @monkeyarmada, @am_hynny, @suzlister, @tullyhansen, @Gold_Ginger, @nidjit, and @rosecrans. Without their help, this would have been meaningless. And not nearly so much fun.